What would Christopher Lloyd be without Great Dixter? Vita-Sackville West without Sissinghurst? Lawrence Johnston without Hidcote? Gardeners make their gardens, but in turn too, gardens make the gardener. Without the legacy of her own incredible garden, the horticultural talent, that is Miss Ellen Willmott, has been forgotten, or simply diminished to the yarn of a prickly old lady who liked to scatter Eryngium giganteum seeds in gardens she visited.

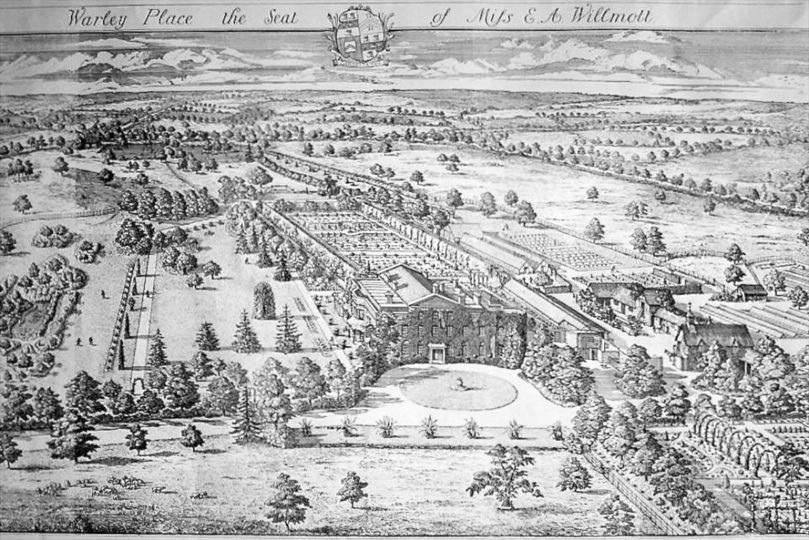

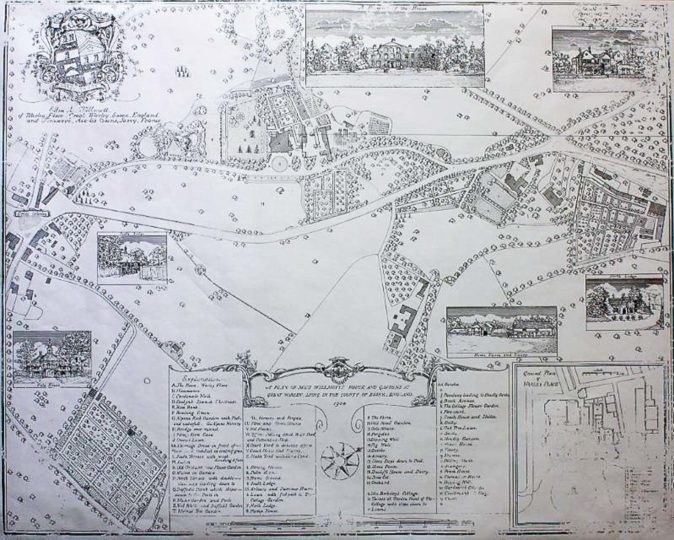

Respected and honoured by her peers, Ellen Ann Willmott; plantswoman, botanist, author and admired gardener, was one of the great personalities of British gardening. Willmott’s thirty acre garden, Warley Place, near Brentwood in Essex was once one of the most beautiful and interesting of English gardens. At Warley, she grew over 100,000 different species and cultivars of trees, shrubs and plants. The new plants developed at Warley, won prestigious RHS accolades and were available for purchase on her annual seed lists. Willmott financed plant hunting expeditions, such as those of Ernest H. Wilson, in return for plants and seed material used to extend her extensive collections. Willmott’s willmottiae and warleyensis cultivars such as Veronica prostrata ‘Warley Blue’, Ceratostigma willmottianum, Aethionema ‘Warley Hybrid’, Potentilla nepalensis ‘Miss Willmott’, Campanula pusilla ‘Miss Willmott’, Syringa vulgaris ‘Miss Ellen Willmott’ are still sold around the world today.

Willmott left us the extraordinary ‘The Genus Rosa’, which stands proud as the twentieth century counterpart of the famous Redouté. With over fifty different cultivars named after (or by her), Ellen Willmott is justly described by Getrude Jekyll as ‘the greatest of all living woman gardeners’. Both Jekyll and Willmott were awarded the Victoria Medal of Honour in 1897, along with other horticultural greats such as William Robinson. Willmott, very much part of the influential horticultural leaders of the day, was elected to sit on (a.o.) Narcissus and Tulip RHS committees, elected member of the Linnaean Society of London, and was one of the three trustees for the RHS Wisley garden, instrumental in obtaining Wisley for the RHS.

Her garden lies sleeping

An abundance of accolades and medals, that’d put even the likes of Michael Phelps to shame, Willmott was one of this country’s most celebrated gardeners, yet she remains overlooked. Her house and garden were demolished long ago, and sadly with it so too, the evidence of her extraordinary planting, garden design, and (rare) collections of plants, shrubs and trees. Unfortunately, Willmott died fourteen years shy of the establishment of the first (RHS and National Trust) Committee for garden conservation and hence, Warley slipped through the net. Much to the credit of Vita-Sackville West, Hidcote was the first garden to be protected, safeguarding Major Johnstone’s horticultural masterpiece for future generations.

Even though of horticultural importance, it is very unlikely that the forlorn ruins of Warley, will ever undergo full historic horticultural conservation. The property, now leased to the Essex Wildlife Trust, is managed by volunteers primarily as a safe haven for wildlife, though when time and resources allow the volunteers carry out selective conservation projects, such as the reconstruction of the wall in the walled garden, replacement of trees, and rebuild of terraces. With limited resources at hand, it is heartwarming to see the enthusiasm of the volunteers and their passion for Warley and Willmott.

Wandering around Warley, accompanied by the knowledgeable John Cannell, a volunteer at Warley, one is immediately struck by the beauty of the place. The proud house has been pulled down to the basement and the gardens are overgrown, but the structure and layout is there. Willmott meant business, much evident in the extensive irrigation systems running throughout the garden to and from numerous large reservoirs, abundant green- and (sunken) hothouses, endless rows of cold frames, hot beds, growing beds, a huge walled garden, several ponds, miles of laid paths, terraces and architectural features such as the summer house, from which she and guests could enjoy the garden. Where the ruins allow, one can clearly see her eye for detail, such as the beautifully paved paths (similar to those at Heligan in Cornwall), extensive conservatory, detailed mosaic floors, grotto-esque stone cladding in the hothouses, delightfully ornamental metal gates, superbly detailed garden walls, all alluding to the gardens’ once former splendour. ‘Her beautiful garden at Warley in its heyday gave pleasure to innumerable visitors and became world renowned’, described William T. Stearn1.

Ellen

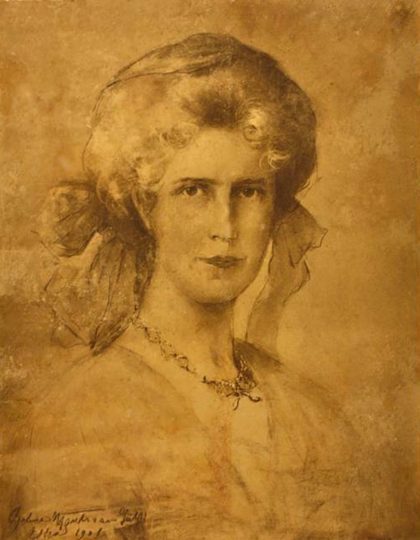

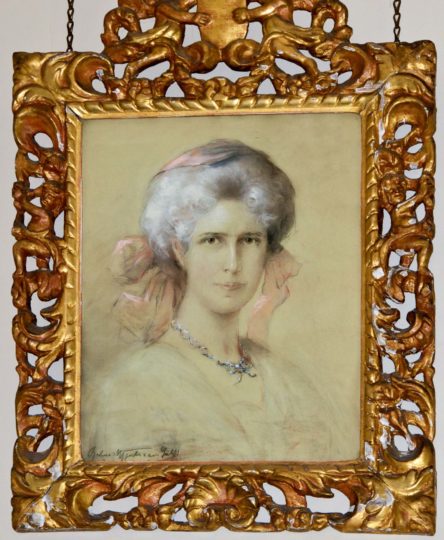

Ellen Willmott was born in 1858, daughter to Frederick Willmott, flourishing solicitor and Ellen Fell of the Tasker family. Frederick and Ellen had three children, Ellen, Rose and Ada, though unfortunately Ada died young of diphtheria. In 1875, the family moved from London to Warley Place; an extensive 30 acre estate with grand house, two lodges, meadows, stream and ponds. Both Ellen and her sister were introduced to gardening by their parents, in particular their mother who, a lady very much after my own heart, was ‘one of the pioneers who broke away from the mid-Victorian tradition of carpet bedding and ribbon borders’. Both Ellen and Rose, inherited their mother’s passion for gardening, whilst as proper ladies of those times, they also excelled in the polite arts, including languages (French, German and Italian), music and painting. ‘She had beauty, intelligence, talent in many ways and the aptitude for complete absorption in whatever she was doing’, stated Graham Stuart Thomas2.

As a successful businessman, Frederick Willmott was able to provide generously for his family, though with the additional munificent annual financial contributions from Countess Helen Tasker (Ellen’s godmother), Ellen had complete flexibility to engage in all the activities of choice, such as photography, carpentry, painting and gardening. These, she engaged with a high degree of skill, dedication and technical proficiency, mostly self taught by trawling her way through volumes of valuable books. She had tools for farrier’s work and carpentry, a lathe, printing press, microscope, telescope and for her photography, photographic plates, film and dark room. Her skilled photographs, a few of which have kindly been provided by a private collector for this post, have appeared in several published books, including Gertrude Jekyll’s ‘Children and Gardens’ (Country Life, London, 1908).

Ellen’s first authoritative gardening foray was the creation of her bold and incredibly imaginative ravine, alpine rock garden. Until seen in person, the enormity of this project is difficult to envision. A deep gorge, once with flowing stream, several pools, waterfalls, and fern caves, walkways, all designed by young Ellen3, then only in her early twenties. The skill in her garden design is clearly evident, as the rock garden beautifully echoes the natural lie of the land amongst the established trees. Furthermore, she ensured all the correct requirements were in place to ensure the optimum soil conditions for her plant choices. The design included a glass walkway over the ravine, so that one could enjoy the stream, pools and fern caves from a different perspective. ‘A stream of water ran through the little valley, keeping it temperate in hard winters, green and moist in hot summers’, explained Audrey Le Lievre in her vividly written biography4.

The lavish and complicated design, attention to detail and undoubtedly astonishing planting very much set the tone for all her subsequent gardening endeavours, where Ellen’s confidence, practical and technical prowess, financial freedom, and desire to have nothing but the best, resulted in not only her much admired Warley Place Gardens, but also two other gardens Tresserve in France and Boccanegra in Italy5.

The consummate gardener

‘My plants and my gardens come before anything in my life for me and all my time is given up working in one garden and another, and when it is too dark to see the plants themselves I read or write about them’, Ellen Willmott6.

Willmott was a studious gardener, and despite employing over 100 gardeners at Warley alone, worked diligently in her garden, rising at dawn everyday. The gardeners reported finding Willmott already working away in the garden with trug and trowel, (trans)planting or weeding, on their arrival for work. The long hours in the open air are said to have made their mark on her increasingly coarse, weather beaten complexion.

Everything in the garden, had to be perfect and the gardeners were under pressure to ensure quality work, even weeding trugs were inspected for mistaken plants. ‘The main problem as the gardeners saw it, however, was that Miss Willmott worked among them, and no one quite knew where she was going to appear next’, wrote Le Lievre.

Willmott knew every inch of her garden. Her notes7 read of detailed assessments of the varieties of daffodil she grew and cultivated. Rogues were destined for the ‘vinery’ border, those that passed her tests were planted in suitable spots, unlucky ones ‘1 bicolour deformed’, were destined for the dump. Detailed surveying of the daffodils and the garden, meant that she knew every plant in every border, ‘to the last bulb in the smallest bed’.

Willmott’s physical strength was legendary, working her garden hard, though when time allowed it, she must have enjoyed her garden too. At Warley, there is clear evidence of several seating areas, summer house, terraces, and arbors throughout the garden. Paths wind around the garden, carefully planned to enjoy the various vistas and at the south end of the garden a huge steel construction was put in place as the foundation for an enormous hill, to ensure she could enjoy her garden in complete privacy.

Talented as she was in the arts, her languages, her photography, Willmott was a gardener. Once asked if she played the organ, as she seemed to have ‘organist’ hands, she promptly replied, ‘No, but I can use a spade’.

Au naturel or bust

Much influenced by the eminent Willian Robinson (1838 – 1935), early practitioner of the the herbaceous (‘mixed’) border, and editor of the precursor of ‘The Garden’ magazine, Willmott planted (hardy) herbaceous perennials in natural drifts, in her densely planted borders, preferably leaving little soil exposed. Taking after her mother, both Ellen and her sister Rose were against the ‘patterned’ Victorian gardening principles, opting instead for Jekyllian, natural, less formal-looking, and ‘wild’ planting techniques. ‘The flowers, shrubs, vines are most beautiful, a wild tangle of loveliness, the most artistically natural, or naturally artistic, thing you ever saw. Of course, there is a great deal of labour and art in it all, but it looks as if nature had her own way8’.

Bulbs too were planted to look natural. ‘The gardeners’ children were persuaded without much difficulty, to throw handfuls of bulbs from a wheelbarrow over the ground-where they fell, there they were planted and there they multiplied’, wrote Le Lievre. English crocus were encouraged to spread using the same techniques on the lawns and fields, and it is said that she also laid seed beneath turf. Camassia too, were popular in her naturalising armour, where according to Le Lievre, one recorded order included some 10,0009 bulbs. That certainly puts my relatively piddly 125 Camassia planting spree to shame.

Green genes

Ellen’s sister, Rose, married Robert Berkeley and lived at Spetchley Park in Worcestershire. Rose, a superb gardener in her own right, created a beautiful garden at Spetchley with the help of her famous sister, and plants off the Warley production line. Uniquely therefore, rare species can still be found in both gardens such as the magnificent Paeonia suffruticosa and the Ginkgo biloba. The latter, an extraordinary specimen, now proudly towers, over the walled garden at Warley.

According to Ellen Willmott, Rose had a great hand at creating herbaceous borders, which she amusingly describing as a ‘rare taste in the effective grouping of plants’. The borders at Spetchley (under renovation on my visit) are spectacular, and though this could just be my viewing the garden through rose-tinted glasses, did seem Willmott-esque. However, this is by no means a strict Rose (and/or Ellen) Willmott garden. On my visit to Spetchley, the charming, John Berkeley, current owner of Spetchley Park (grandson of Rose), explained that in his view ‘Gardens must never sit still and are therefore transient’. Since the Rose (and Ellen Willmott) reign, Spetchley has therefore undergone, and will continue to undergo, change. A visit is highly recommended.

The Money

Apart from the delightful biography ‘Miss Willmott of Warley Place: Her Life and Her Gardens’ by Audrey Le Lievre, relatively little has been written about Willmott. Unfortunately, much of what has been published tends to be dominated by Willmott’s infamous riches to ruin story. She did indeed spend her extensive Willmott and Countess Tasker fortune, and even managed to run into debt, to the unfortunate cost of her lovely gardens, properties and possessions. Though, Willmott’s horticultural talents and legacy far outweigh her lavish spending habits.

‘Money in itself was of no interest to her: she cared for it only in its creative capacity’, writes Le Lievre. According to Jane Brown10, Frederick Willmott did his daughters a great disservice by giving them the impression that they would never need to soil their hands with financial management, which in those days was probably common practice. ‘If Willmott pere had been less indulgent, if he had given her a better education and put a business head on her shoulders, then maybe we should have Warley still’, writes Brown. Very much accustomed to a sumptuous life style, Willmott’s reckless spending was thoughtless, indicative of the way she lived and her desire to have nothing but the best. William Robinson wrote to her in August 1910 ‘I have always been greatly impressed by your expenditure and thought that only a millionaire could afford it. The way you get into trouble is to have several homes’11. Considering that she expected the same standards for all three of her properties and gardens, Robinson had a valid point.

Her financial foolishness, which is by no means excusable, was fueled by her passion for plants and her gardens. Admittedly, as any passionate gardener will admit, she is not alone. Granted she had more cash and spent more than most, but as my credit card statement shows after a visit to a Crocus Open Day, plant fair or show, nursery or simply browsing online or through catalogues; when purchasing plants and/or bulbs, any financial reasoning is quickly forgotten. With a more generous bank account and shinier credit card, I too, could certainly do some serious damage.

Legacy

Willmott died alone at Warley in 1934, from a presumed heart attack. The last decades of her life could not have been easy, watching her beloved Warley steadily overgrowing and selling personal possessions in an attempt to plug her hemorrhaging finances. Worse still was the death of her sister Rose, in 1922. Rarely caught off guard, the grieving plantswoman poignantly said ‘Now, there is no one to send the first snowdrops to’12.

Her story does not end with her death, as Willmott has made an irrefutable mark on horticulture in; the horticultural honours she received, literary achievements, her reputation as a cultivator and plant collector, champion of plant hunting expeditions, creator of incredible gardens at Warley Place, Tresserve and Boccanegra, and of her friendships and collaborations with the horticultural elite of the day. Presumably though, she’d be the most proud seeing those plants in gardens, garden centres and nurseries across the world, labelled with that magic name; Willmott.

The loss of her gardens, especially Warley is a tragedy. Despite its beauty as a wildlife conservation area, one can’t help but wish to see it returned to its former glory. I end therefore, with a small plea to the world of horticultural and conservation; Warley could be the next Heligan……

- Stearn, W.T., ‘Ellen Ann Willmott Gardener and Botanical Rosarian’, The Garden Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society, June 1979, vol.104, part 6, pp.241-246

- Commentary in ‘A Garden of Roses’, by Graham Stuart Thomas OBE VMH DHM VMM. Source ‘A Garden of Roses: Watercolours by Alfred Parsons’, Pavilion Books, 1987

- The excavation and construction of the rock garden was done by James Backhouse of York.

- Audrey Le Lievre, Miss Willmott of Warley Place, Her Life and Her Gardens, Faber & Faber, 1980.

- Ellen Willmott purchased Tresserve in France in 1890, and Boccanegra in Italy in 1905.

- Audrey Le Lievre, Miss Willmott of Warley Place, Her Life and Her Gardens, Faber & Faber, 1980.

- Audrey Le Lievre, Miss Willmott of Warley Place, Her Life and Her Gardens, Faber & Faber, 1980.

- Letter dated 18/09/1900 by Lady Wolseley to her husband on visiting Willmott’s garden at Tresserve in France. Source: Betty Massingham, A Century of Gardeners’, Faber and Faber, 1982.

- Recorded purchase from the wholesale bulb and seed merchants in Covent Garden; J.D.F.W & Co

- ‘The Essay: Miss Willmott’s Ghost’, Jane Brown, 11 september 1999, The Independent.

- Audrey Le Lievre, Miss Willmott of Warley Place, Her Life and Her Gardens, Faber & Faber, 1980.

- Audrey Le Lievre, Miss Willmott of Warley Place, Her Life and Her Gardens, Faber & Faber, 1980.

Note: The photographs taken by Ellen Willmott, were kindly provided by a private collector.