‘Paradise haunts gardens’ writes Derek Jarman, ‘and it haunts mine’. In the gardeners ceaseless pursuit of horticultural perfection, one can become blind to the beauty of the garden, detecting nothing but its faults or maddeningly triumphant weeds. Taking stock should mean more than simply registering the new list of tasks that need to be taken care of. Never did I anticipate that the presence of canvas, paint and brushes could teach one to really look at the garden, and appreciate that imperfections, though seemingly wrong, are very right indeed.

Man in the hat

Armed with hat, easel, bag full of paint and brushes, contemporary British artist, George Irvine, arrived to put the garden to canvas. Once the youngest artist to grace the Royal Academy Summer Show, the Slade trained artist, is well known for his unique painting style, incorporating strong brush work and skilled use of bright colors. His paintings, often depicting his proud sense of Oxfordshire terroir, demonstrate his passion for painting and uncanny ability to depict the true essence of his subject.

Irvine returned to his much loved former school, Stowe, where for more than a decade he was key in establishing what became the best secondary level art departments in the country. He felt the time had come to bring the attention back onto his work and own budding art school at the delightful Buttermilk farm, and therewith end his successful stewardship of the Stowe art department. An ardent admirer of his work, the notion of our garden becoming part of Irvine’s portfolio was simply too exciting for words.

The garden into art

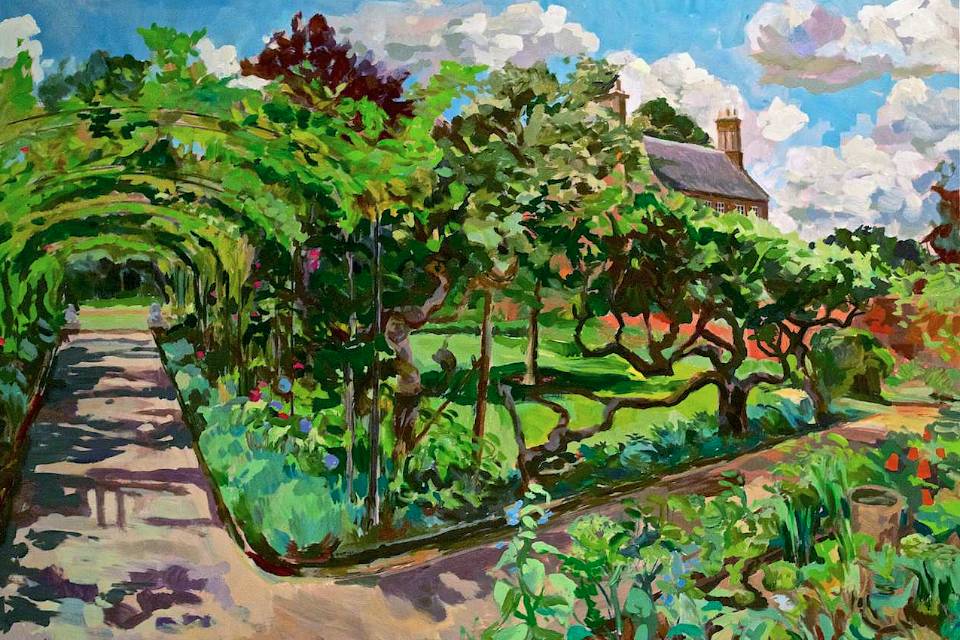

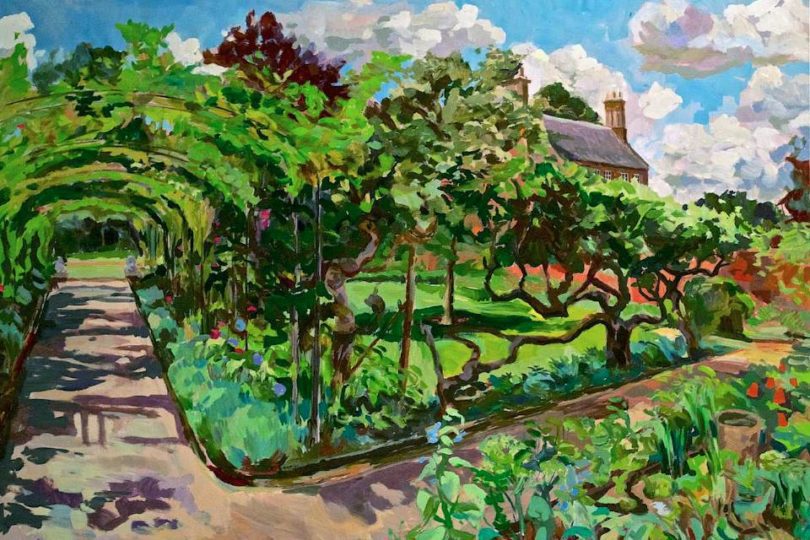

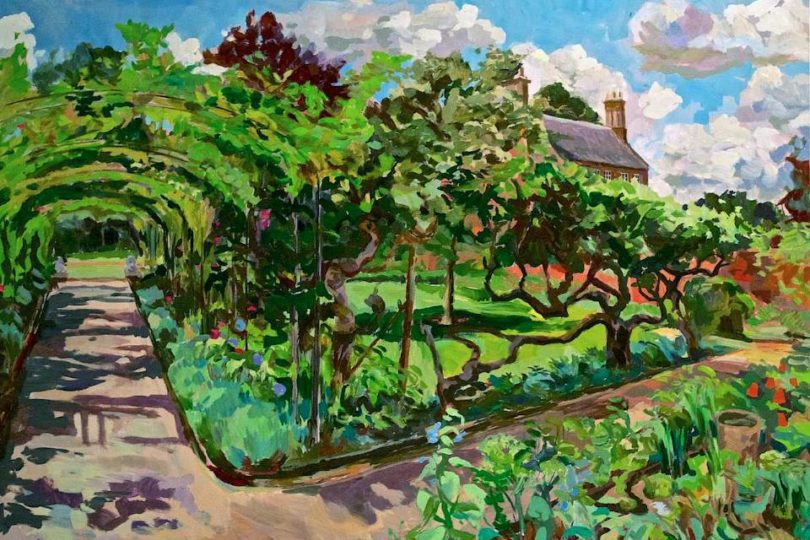

Often gardens are only depicted as the foreground to a beautiful landscape, but Irvine looks to the garden itself as the source of inspiration for composition and colour. ‘As well the character of the garden, I like the impression that you are going somewhere, that the garden is leading you out, onto the next thing. Sometimes you need to push the composition to bring that across’, explains Irvine, opting for two specific views to plant his easel.

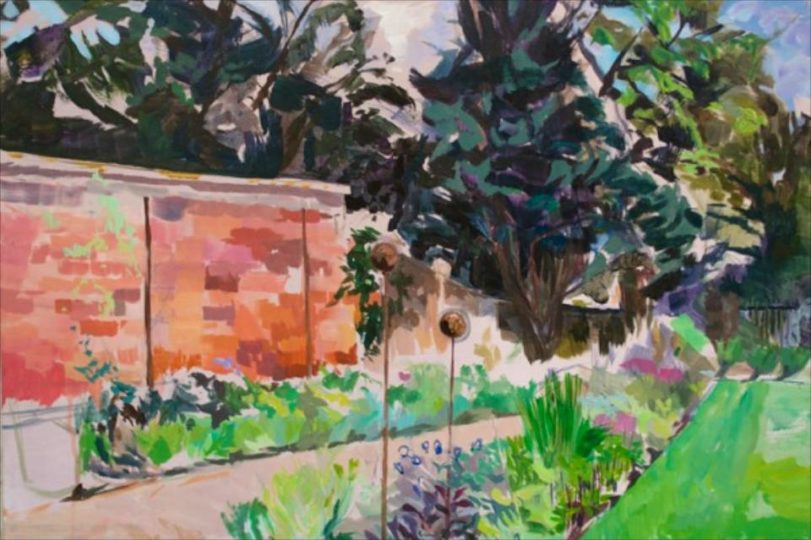

As a composition, traditional old gardens are favourite for Irvine, though in particular working gardens and allotments. ‘There is something special about that process of cultivation and the general workings of a garden. Vegetable gardens, orchards, greenhouses are just beautiful’, says Irvine. A sentiment much echoed by Stanley Spencer in his ‘Greenhouse and Garden‘ work (1937) and Eric Ravilious ‘The Greenhouse: Cyclamen and Tomatoes‘ (1935). ‘Having said that I love gardens full of wild flowers, and things coming out of the gravel. Controlled chaos I suppose. Natural as if it should be like that’. Thankfully, as Derek Jarman wrote, ‘If a garden isn’t shaggy forget it’, and shaggy is the name of the game, chez nous.

Irvine’s garden paintings are very different from the archetypal Edwardian and/or Victorian water colour, raising the subject beyond the merely pretty. The Victorian and Edwardian era of garden painting, accomplished and enchanting as works may be, lack that liberated artistic force. Alfred Parsons paintings of Ellen Willmott’s Warley Place and his own garden at Luggers Hill for example, though superb are the exact embodiment of the garden, down to the last flower. Much in agreement with Jane Brown, author of the fascinating ‘The Pursuit of Paradise’, Irvine feels that significant British garden art begins with modern painters, and is a staunch admirer of the work of Patrick Heron and Ivon Hitchens. ‘I love their abstract expression, using just colour and light’, explains Irvine.

Artist turned Gardener

The analogy between painting and gardening has always run deep, where both require effective composition, proportion, texture and colour. ‘Experimenting is what art is all about, as it is in gardening and I find myself fast becoming more of gardener. Pushing the boundaries as to what can be done with different mediums, is exciting and particularly fun to do so with plants’.

Gardening greats such as William Andrew Nesfield (1794-1881), Getrude Jekyll (1843-1932) and Alfred Parsons (1847-1920) all began their careers in painting, though it was in their field of gardening that they achieved their deserved prominence. Painting alone does not provide the recipe for a good gardener, but the affinity between the two is undeniable, ‘Just as in my painting, when I garden I look for a range of sharpness, slants, mat surfaces, opportunities for light to shine through, and this all through the year where plants do extraordinary things’, explains Irvine.

Reversely too, according to Irvine, being a gardener makes a better garden painter. ‘One can certainly detect a sensitivity to the process involved in gardening in painting along with the excitement of planting, seeing it grow, and the love of the earth’, he explained. ‘It must have been so exciting for Claude Monet, that once he started to make some money, he was able to put that back into his garden and subsequently his art, generating the vision that was his garden. That cycle of the garden into art, is wonderful.’

The Artist Eye

William Robinson (1838-1935), founder of The Garden (1871) and Gardening Illustrated (1879), prominent critic of the formal garden style, strongly advocated that gardeners to take the lead from painters and learn how to compose gardens pictorially. ‘Wandering through Monet’s garden at Giverny, planted a seed in my mind of an artist making a garden in view of his art, an idea that I simply love. My gardening involves adding bold colour, texture and interest throughout the year where in winter their seed heads reign’, explains Irvine.

At Buttermilk Farm, Irvine’s home in Oxfordshire, hedges, trees are cut and/or planted to create views through to the much loved landscape. With much excitement, he has also revealed ambitious Stowe-esque plans to build a ten foot long ha-ha, to bring that landscape in closer, and merge the garden seamlessly into its stunning views. ‘Traveling through, along and out. I like coming round the corner seeing the Bloxham spire, slightly framed’, explains Irvine. With a nod to Monet, Irvine’s shares his garden with aspiring painters and is subsequently home to the students of Buttermilk art school, where painting ‘en plein’ air is very much the order of the day.

In his garden, Irvine plants strong colors side by side, rather than opting to blend. ‘In my garden, bright colours are key to catch the eye and help create a more interesting juxtaposition. I suppose I subconsciously apply Goethe’s theory of colour, but I like to contrast, adding orange poppies where one least expects it’, explains Irvine. ‘Garden in a way that is personal to you, that is what I do anyway’, he said painting a humble breeze block, which is to become a sculpture for the flower borders.

Digital Drawback

The digital camera is a marvel, and certainly chez Oxonian my camera has very much become one of the garden tools, documenting progress year on year. Though, as with all progress, there are drawbacks as we now idly take fifty odd photographs, without really batting an eyelid, nor taking the time to set up, find that perfect view, composition or required light condition. After all, Photoshop (or equivalent) will deal with what ever is wrong with it later.

My ever swelling image library, clogging up my hard drive, is certainly a good record, but has it captured the essence of the garden and/or the intended planting effect? Watching and listening to Irvine initially decide on his vantage point, and eventually paint, marveling at the various green shades of the foliage, distinguishing how flower colours interact with light, shade and texture and pick up details that I have long since stopped or never noticed before, I feel almost estranged from that garden in which I thought I knew so well. ‘Painting pushes you to look at your garden. Even if armed just with a sketch book, one is forced to make decisions about the colours, detail, texture, shadow and how things actually look, even on the greyest of days. Something you think you do everyday, but its often not the case, until you really need to make the decisions, to mix the colours, and put your brush to the canvas’.

According to Irvine, anyone can paint. ‘Just think back to the Victorian era, where everyone had to learn to speak various languages, play an instrument, and paint. More people should learn to paint, it’s truly cathartic’, beamed Irvine. Invigorated and enthused, I put Irvine’s ‘We can all paint’, to my husband, who replied, ‘Ah yes, but the question is, should everyone be allowed to paint?’. Back to my camera.

Photographs of George Irvine paintings are copyright George Irvine. To see more of George Irvine’s incredible portfolio and Buttermilk Art School, I refer you to his very dishy website, built by my husband and yours truly (impertinent plug)….